Sin categorizar

Influences and ingredients in Burmese food

“International demarcations are a relatively new system that has only existed since the formation of nation states. Remember, until the latter half of the 20th century, most of the world was still wide-open territory with loosely or undefined boundaries“

Abigail Vandenbergh, September 2023

American Geographical Society

When we talk about the origins of a country’s food, its neighbours play an important role. Burmese food is clearly influenced by the proximity of Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand. The way we eat transcends borders that are often closed to people

Burma (today Myanmar) is a big country with a land area larger than France and a varied climate, from tropical beaches in the south to mountainous areas susceptible to snowfall in the Northern areas of the lower Himalayas

There are more than one hundred ethnic groups recognized by the central government. This combination of cultural and geographic diversity creates an equally varied regional cuisine. But there are common threads in this diversity and ingredients that crop up again and again in dishes across the territory. These are the basic supplies we need if we are to try and reproduce at home some of the better-known dishes from this fascinating country.

At Ma Khin we are advocates of what we call Decolonial Food. Using local produce, we adapt and transform dishes from other parts of the world and take ingredients and culinary practices from distant places to renew and reinterpret local recipes.

For us, both Burmese and Mediterranean food are constantly evolving, so do try experimenting with local alternatives if you can’t find any of those listed here. Happy cooking!

Rice

Rice is the staple ingredient of Southeast Asian and Burmese cuisine and Burma was once the world’s largest exporter of rice.

But disastrous economic policies in the second half of the 20th century and a lack of investment have made Burma dependent on rice imports. The poor price paid by international markets for relatively low-quality Burmese rice means you are unlikely to find a packet on your supermarket shelves. Thai fragrant rice is a good alternative.

Ngapi

The use of fermented fish products is ubiquitous in Asia and interestingly was once equally common in the Mediterranean.

The Romans were great consumers of garum, salted mackerel and tuna guts, fermented and dried in the sun before being pickled in brine.

In Burma, ngapi is a generic term for ‘pressed fish’, which may be made with shrimps or fish. You can buy fermented fish paste in Chinese supermarkets.

Keep it in the fridge tightly sealed (it smells dreadful), and before using, wrap it in tin foil and dry roast it in a heavy frying pan. Ngapi is an essential ingredient in balachaung and many Burmese dishes from the coastal areas.

Fish sauce

In a similar process to the production of ngapi, fish sauce collects the liquid result of the process of fermenting fish.

Small fish and shellfish are heaped into concrete tanks and the liquid produced as it all ferments, flows off to be filtered, boiled and bottled

Chilies

In Burma, pregnant women are advised not to eat chilies as they are said to cause baldness in babies!

It is hard to imagine that prior to Columbus’ voyage to the Americas in 1492, chilies were unknown in Asia.

How different the region’s food must have been before the arrival of these addictive little devils! Green and red chilies are used fresh, in salads and stir fries. In Burma, dried red chilies are soaked and pounded with other ingredients to make curry pastes, and chili flakes are usually present on the table to add a sprinkling to a bowl of Shan noodles or mohinga.

Spices

In visits to Burma I’m always surprised how limited is the use of spices.

Chefs prefer the pungent flavours of ginger, shallots, chilies, ngapi and fermented soy paste. But the Muslim population of Yangón inspired by the culinary traditions of India have added biryani, dahl and samosas to Burma’s gastronomic repertoire. Turmeric, cumin, coriander, mustard seeds and paprika are the most commonly used spices.

Invest in a coffee grinder and toast whole spices in a dry frying pan before grinding them.

You’ll be amazed just how intense the aromas are compared to packets of ground spices that may have been sitting on a supermarket shelf for months.

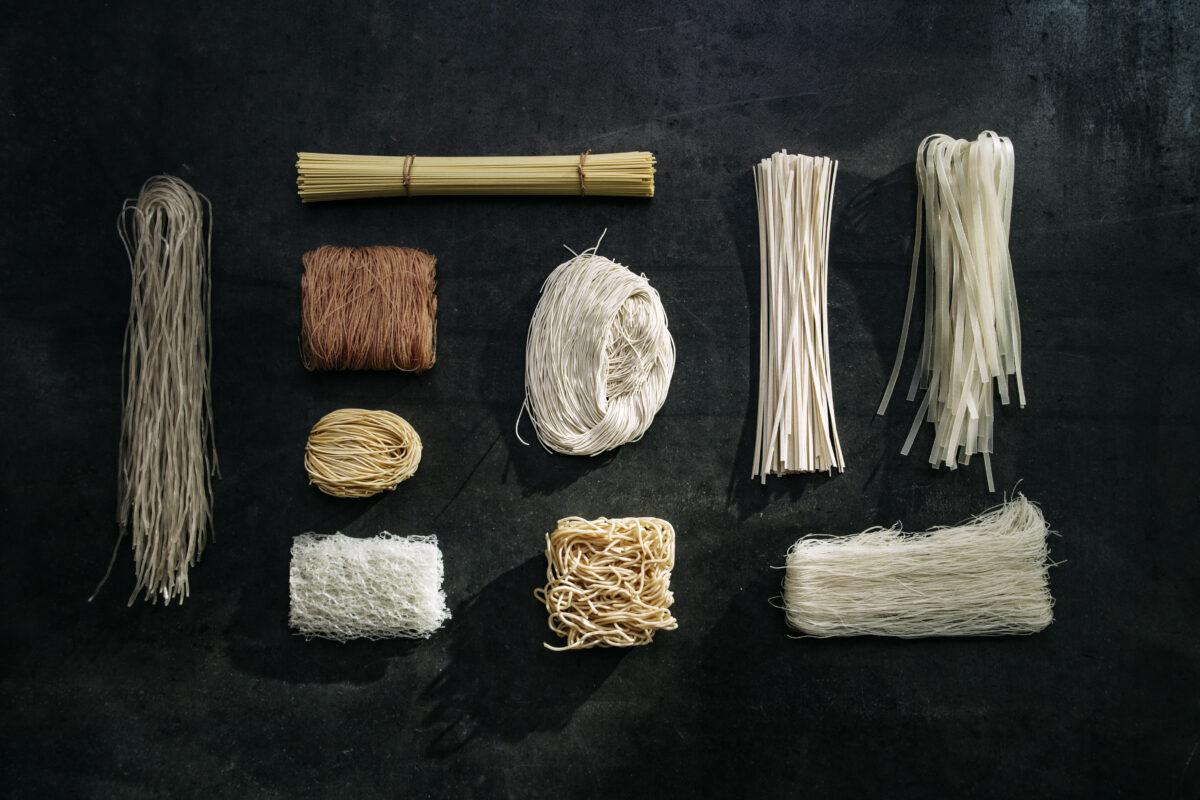

Noodles

I wish we were able to buy fresh noodles in Europe in the same way that we can buy fresh pasta.

On a recent trip to Vietnam, I really appreciated the texture of fresh rice noodles in bun cha and cha ca. Likewise the delicate spring roll wrappers for poh piah rolls that we ate in downtown Yangon. But cooking is often about making do with what you have, so make appropriate use of the dried noodles which you can find in Chinese supermarkets.

Mediterranean vegetables in Burmese food

Maha Bandoola Street in Yangon’s Chinatown is one of the city’s biggest food markets and a feast for the senses.

Enormous crayfish as big as your forearm, prawns the size of a dinner plate and piles of fried crickets vie for your attention alongside stacks of recently plucked chickens whose living companions cluck miserably under wicker baskets. ç

And for the fainter hearted, piled high on carts, a vast selection of tropical fruit and vegetables. Stinking durian sit alongside the more palatable jack fruit and mangosteens, with their thick fibrous skin concealing tender white segments that are wonderfully sweet, acidic and fragrant.

Mangoes are harvested ripe as they should be, and tiger nuts are used to make a refreshing milky drink similar to Valencian orxata. And keep an eye out for Burmese grapes, more like a fibrous lychee than a grape, which can be peeled and eaten directly or fermented into wine. There are aubergines, from the tiny pea variety to the white bulbous and aptly named eggplant. Bitter gourd, wing beans, okra, green tomatoes, and all kinds of leaves: sour, bitter, and fragrant.

At Ma Khin we try as far as possible to use locally produced fruit and vegetables, fortunate as we are to enjoy enormous variety in what is known as the garden of the Mediterranean Coast. Why bring vegetables from the other side of the world when recipes can be adapted to use local ingredients? Many Chinese vegetables are now grown locally, and at my allotment in Valencia I have had great success with lemongrass, long purple Chinese eggplant, and bitter gourd.

Ginger, shallots, and garlic

These deserve a special mention as they crop up repeatedly in many Burmese recipes.

The Burmese use crispy shallots and garlic to sprinkle on salads and soups.

- You can make them by half filling a suitable pan with neutral oil. Drop the shallots begin to bubble.

- Now lower the heat as you need to maintain this temperature (about 160ºC) for the shallots to lose their water.

- If you go too fast, they will caramelise on the outside while remaining soft inside.

- Stir frequently so that the shallots brown evenly.

- After about ten minutes when they have turned a dark golden brown, strain through a metal sieve placed over a clean pan.

- Shake the shallots out of the sieve onto several layers of kitchen paper to drain them of any excess oil.

You can store crispy shallots in an airtight plastic container.

The same process can be applied to make crispy garlic.

The sweet and flavour-filled oil left after frying crispy shallots and garlic can be used for dressing salads

Dried shrimp

Another essential to our store cupboard is dried shrimp. You’ll find these in the cold section of your Chinese supermarket. They should be pink and not a tired brown, though beware of anything that looks excessively and artificially rosy!

In Asian markets shrimp are graded by size, the bigger being the more expensive of course

Nuts and oil

Peanuts and peanut oil are commonly used throughout Asia. Sunflower or rapeseed oil are suitable alternatives as both have a neutral flavour.

Olive oil is not suitable for Asian cooking as the wonderful fruity flavour simply doesn’t fit in.

Sesame oil with its characteristic nutty taste is for specific dishes only and is not suitable as a general-purpose oil.

Fish

The Burmese are huge fans of freshwater fish, not surprising in a country crisscrossed by great rivers.

But the availability of wonderful Mediterranean fish in Valencia has led me to adapt recipes to what I find easily available here. I hope my grandfather K will forgive my use of sea bream instead of catfish in mohinga – an abomination in his eyes! – but having eaten both the authentic Yangon version and my own, I’m inclined to stand by my preference.

Meat

In contrast to Europe and North America, meat is a less important part of the daily diet for many people in Southern and Southeast Asia. When meat is consumed, flavour is hugely important.

I’d recommend investing in a small charcoal grill, which is probably the fastest way to get an authentic smoky Asian taste to your meat. If a barbecue is too much trouble, try seasoning the meat with smoked salt, which is available in many supermarkets.

The content of this article is taken from Burma: Food, family and conflict. Copyright ©:2018, Bridget Anderson and Stephen Anderson

.png)